Show me your vowels!

L’accent écossais, ou : comment analyser les voyelles quand on a du mal à bien les distinguer à l’oreille nue.

This is a bit of a side-piece to the investigation into the pronunciation of the and a — reduced or unreduced? in which context does which form occur? My previous posts are here and here, Mark Liberman’s principal ones here, here, here and here, and David Beaver chipped in here and here.

Looking into when a speaker says [ði] or [ðə], [ɛj] or [ə], or something in the middle, like [ðɛ] isn’t a hard task. You just have to listen to a recording and write down what is said and how, right? Well, yes, if you can indeed hear what’s going on in someone’s speech.

So I was digging up speakers of not-quite-mainstream English accents, and was stumped by Mark Hunter, a Glaswegian who has a podcast on Scottish music. There were two problems with his clips: First, “The Tartan Podcast” is stunningly good, and I was tempted to just listen to the spectacular rock music#[1]. Second, and more seriously, I couldn’t for the hell of it decide when Mark Hunter’s articles were reduced, and when he was employing unreduced vowels.

This is not a problem of understanding what he is saying. Understandability is very much a subjective thing, and indeed I find Mark Hunter’s speech rather euphonious, and much easier to transcribe than others I’ve listened to; for some reason it’s some Californians who require more concentration from me than others — it’s a question of being used to hearing a particular accent.

No, the difficulty came from me not being able to distinguish clearly between his instances of [ðə] and [ðɛ] and [ðʌ]; there’s even a [ði] here and there, along with other vowels, but just by ear it sounded random and all over the place, even before vowels. I was quite unable to tell by ear which of these vowels would have to count as reduced and which as unreduced.

There’s a more technical way of looking at sounds: to plot the principal frequencies in a diagram. With the canonical orientation of the axes of the plot you get a vowel chart — see for example the collection of vowel charts for a number of European languages on the University of Helsinki site: each vowel phoneme of a language occupies its own area of the plot; those along the top are called “high”, those at the bottom “low”; left is “front” and right is “back”.#[2]

Doing this for the vowels of the in a small (3 min) excerpt of Mark Hunter’s speech, we get this:

Well, Glaswegian is obviously more complicated than that. The before arts, artist, ultimate and answer has a vowel that’s in the area of [ʌ] or even [ɑ]. Apparently, the before vowels — and some consonants, like /m/ and /w/, gets assimilated to the next vowel-like sound in the following word (vowel-like, because /w/, which sort of sounds like [ʊ], counts as well). A fair number of the vowels are also realized as diphthongs, sliding from one value (around [ə] most of the time) at the start of the vowel to another at the end. And they aren’t any longer than normal for that — pretty short actually, around 50ms.

And that’s pretty hard to hear. Short of making spectrograms of each vowel, I’m not sure how to find unreduced articles in unexpected places. It’s a mess.

As a point of comparison, I wanted to hear (and record) the same words pronounced by speakers of more standard dialects. Since I live in France, finding a native speaker of English would have been a hard task if it hadn’t been for the wonders of Internet Relay Chat. John “DogBoy” Tocher (male, originally from San Francisco, now living in Huston, Texas) and Stephane Miller (female, originally from the Midwest, now living in Australia) were kind enough to record themselves saying the words on the labels in the above chart and sending me the mp3 files.

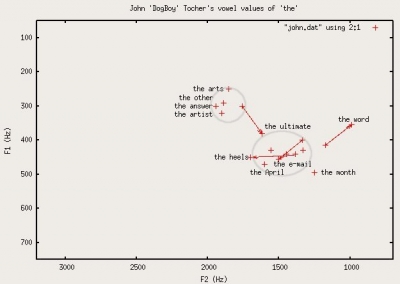

The method is far from ideal, though, because reading out isolated word combinations is quite quite a different task than spontaneous speech. But still, let’s have a look at John’s vowels:

That’s more like it! We still see the “sliding” in the ultimate, from the [i] of the unreduced the towards the vowel in ultimate, and the effect from words starting with /w/, but at least the artist, the other, the arts and the answer are firmly in [i] (or [ɪ]) territory, where we’d expect to find them.

Strangely, John pronounced the April and the e-mail with a reduced article. This may have been due to the artificial character of the exercise.

Now Stephane’s recording stumped me. I won’t even plot it: she pronounced every single the with a reduced vowel, i.e. [ðə]. This had to be an artifact, right? Still, I went back to her and asked whether she always spoke that way, and she replied that she thought she did, except when talking about “Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth” (see also this Google search) because, as she said, “the spelling is weird”. Be that as it may, this is at least one more item on the list of thee subcultures (and I have yet another one, which I’ll blog later).

Back to Mark Hunter and his Scottish vowels. He must have gotten a few remarks on his accent from his listeners and other podcasters. Which is why he is offering some advice on “how to cope” with his accent. And sound advice it is. Listen to it here (lo-fi mp3). This was in his Tartan Podcast number 15 — and he’s at number 48 now.

Okay, I’m off listening to the Tartan Podcast Sleepy Sunday Show…

[1]: If you are into this check out Gum, Electrum, Finniston, Team Salt, Ally Kerr, Miss The Occupier, Conestone… I’d buy a CD by any of these singers and bands in a blink. [2]: This page on the University of Manitoba site has a very nice and gentle introduction to English vowels. I have also been collecting links to phonetics/phonology resources on my wiki — thanks to whoever corrected a spelling error there some months back.

Related posts: Thy "thee"s, Ed Felten..., No word too small, More Scots, Edwardian phonetics., France - accents, BBC "Word 4 Word", Non-eggcorn: "equilateral(ly)"

Technorati (tags): accent, English, language, linguistics, phonetics, scottish accent, speech analysis

- vowel values of ‘the’” title=”Glaswegian accent (Mark Hunter) - vowel values of ‘the’” /></a></p>

<p>(<del>Sorry if the plot is too wide for some displays. You can always right-click on the image and choose “view image”, or whatever your browser’s context menu calls it.</del> UPDATE: replaced with thumbnail with link to full size, as Internet Explorer has problems with overlarge boxes.)</p>

<p>The purple squares are instances of <em>the</em> before vowels, and the red, green and blue crosses represent occurrences

before different types of consonants. The cloud of green crosses in the middle is about where Mark Hunter’s nondescript <span class=) [ə] is located. But what about the unreduced articles, which are supposed to occur before words starting with a vowel, sound like

[ə] is located. But what about the unreduced articles, which are supposed to occur before words starting with a vowel, sound like